The Bourgeois Century

Louise Bourgeois at the Museum of Modern Art

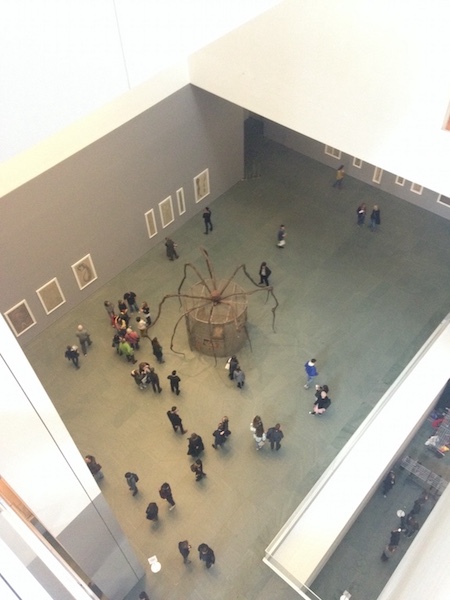

In this show of Louise Bourgeois’ works on paper at the Museum of Modern Art it is unclear if the titular “unfolding portrait” is one seen from the outside looking in or vice versa. As far as female artists go, Bourgeois is certainly well known, but I wouldn’t be surprised to learn how few people visiting the exhibition were familiar with her work beyond her monumentally chilling spider sculptures, if even those. This prompts me to say what is “unfolding” here is the museum’s (or, even better, the museum world’s) interpretation of Bourgeois and not Bourgeois’ understanding of her own self, as the themes of entrapment, motherhood, cruelty, and pain, though expressed through an impressive set of media (from printmaking and sculpture to textile and miniatures) remain remarkably consistent throughout her decades long career.

What emerges as a theme in this exhibition, on view until the 28th of January, is artistic process as personal discovery. In most sections (labeled, among others, “Architecture Embodied” and “Spirals”) are clusters of prints, displayed to show Bourgeois’ process of working and reworking images to ultimately conclude with what the museum has labeled the “final” version. Why these multiples of one image are an insight into Bourgeois’ specific artistic development rather than just how any work of art must get made is not discussed in the exhibition’s literature. (I found the most value was added in showing the prints’ iterations in the multiple versions of her piercing Sainte Sebastienne, which varied so drastically as to give you an insight into the artist's varying mental states.)

While building is certainly a theme in Bourgeois’ work, so is unbuilding. It was only in her 80s that Bourgeois began incorporating textile into her process. This is remarkable not only for the courage required to grapple with new tools at such an age, but particularly for the success of these works, as I found myself surprised to note that many were made in the last decade of her life, all the while feeling they were among the strongest and most confounding of the exhibition.

“Unfolding” implies expansion, revelation. Bourgeois’ productivity was seemingly endless (to which the large quantity of textile work produced late in her life attests), but in no way do we get the sense that her work culminates in anything—nor should we expect it to. We build our lives up, up, up; we add to a body of work, we build our houses, we acquire scraps of clothing with which we fill our closets, and eventually all it comes to is a cluster of buildings, a closet stuffed with clothes, a pile of papers. Using textile was not a mode to express what it means to be female (for which the textile art of the 1960s certainly aimed), but rather was a practical use of preexisting material: Bourgeois simply had an excess of fabric accumulate over her lifetime, and she intended to make use of it.

Hours of the Day, a fabric book from 2006, expresses these themes in a single page, which lies open in an exhibition case. Embroidered in red thread are the lines “What did you do for twenty years?/ You have wasted your time/ Woman has lost her life.” While many of her themes are universally recognizable (like the frustrations of motherhood which drive these lines), the expression of them is singular to her. For Bourgeois, childbirth and motherhood do not seem to be a renewal or rejuvenation of life (her three sons are rarely invoked personally ), but rather additions to a life specific to the artist. Many of the “pages” of the fabric books on display are fashioned out of old “LBG” monogrammed linen napkins from the Bourgeois-Goldwater home, stamping the fabric with her signature, and by doing so forswearing reference to the anonymous women craftspeople her fiber arts contemporaries often honored in their own textile works. Bourgeois’ own expression is born from herself and does not claim to represent all.

There are many repeated motifs in Louise Bourgeois’ oeuvre, among them the arrow, which acts as an ideal metaphor for the artist’s oeuvre as a whole. Bourgeois’ life was an arrow that traveled through space for a blessedly long time (she died at 98 years old), which fashioned itself into an impressive body of work. The arrow has direction, but hurtles on deriving visual energy from itself and not the space through which it travels.

The show ends on a set of impressively large prints from her series À l’Infini (To Infinity) made by a technique through which large format prints could be reproduced, which Bourgeois would then alter with unique additions of gouache and ink, bridging the gap between reproduction and variability. It is the ultimate show of artistic self-regard, to claim that infinity can be born of the singular, unique, and prolific artist, if only she were not limited by the confines of mortality. I have no doubt that if Bourgeois were granted the gift of everlasting life she would never tire of her process, never cease to supply us with her deeply uncomfortable, moving art. And, frankly, I would never tire of consuming it.

Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait

Museum of Modern Art

11 W 53rd Street, NY, NY

On view until January 28, 2018