Little Known Folk

Pearl Blauvelt and Janet Sobel at Andrew Edlin Gallery

The artists’ status as “self taught” (as well as their shared birth year of 1893) is the unifying principle at Andrew Edlin Gallery, which has on display two concurrent solo shows of the artists Janet Sobel and Pearl Blauvelt.

Interest in folk art picked up steam in the 1930s, as it was appealing to Modern sensibilities for its wonky perspective.* But while it is tempting, justifying so-called outsider art’s significance as if it were “modern” (rather than modern-sympathetic) often devolves into meaninglessness, as these artists’ engagement with the Modernist tradition was largely absent. (After all, many folk artists of interest in the early 20th century were born and dead long before the birth of Modernism.) Rather, whatever ends up on paper (or canvas) was often simply the best the artist could do, as they lacked formal training.

Pearl Blauvelt, Untitled, c. 1940's

Graphite and colored pencil on notebook paper

Pearl Blauvelt’s work was discovered by the artists Donna and Dennis Corrigan in their newly purchased home, long after the artist had died. Little is known about her life, but the few the details of her living situation (alone, with her father in rural Pennsylvania) tempt us with the familiar story of the reclusive, socially awkward, and mentally ill adult artist. Such speculation, however, can only serve to cement stereotypes that bring us farther from what we do know, which is some 800 drawings on notebook paper of various scenes of American life.

The feeling that Blauvelt’s work has nothing to hide is literalized in her compositions, which go out of their way to tell, not show. Objects rarely overlap and many surfaces are depicted as if seen from multiple perspectives simultaneously, defying rules of optics. (We see, for example, a horse drawn carriage from a bird’s eye view, though the rest of the scene is from the perspective of a person by the side of the road.)

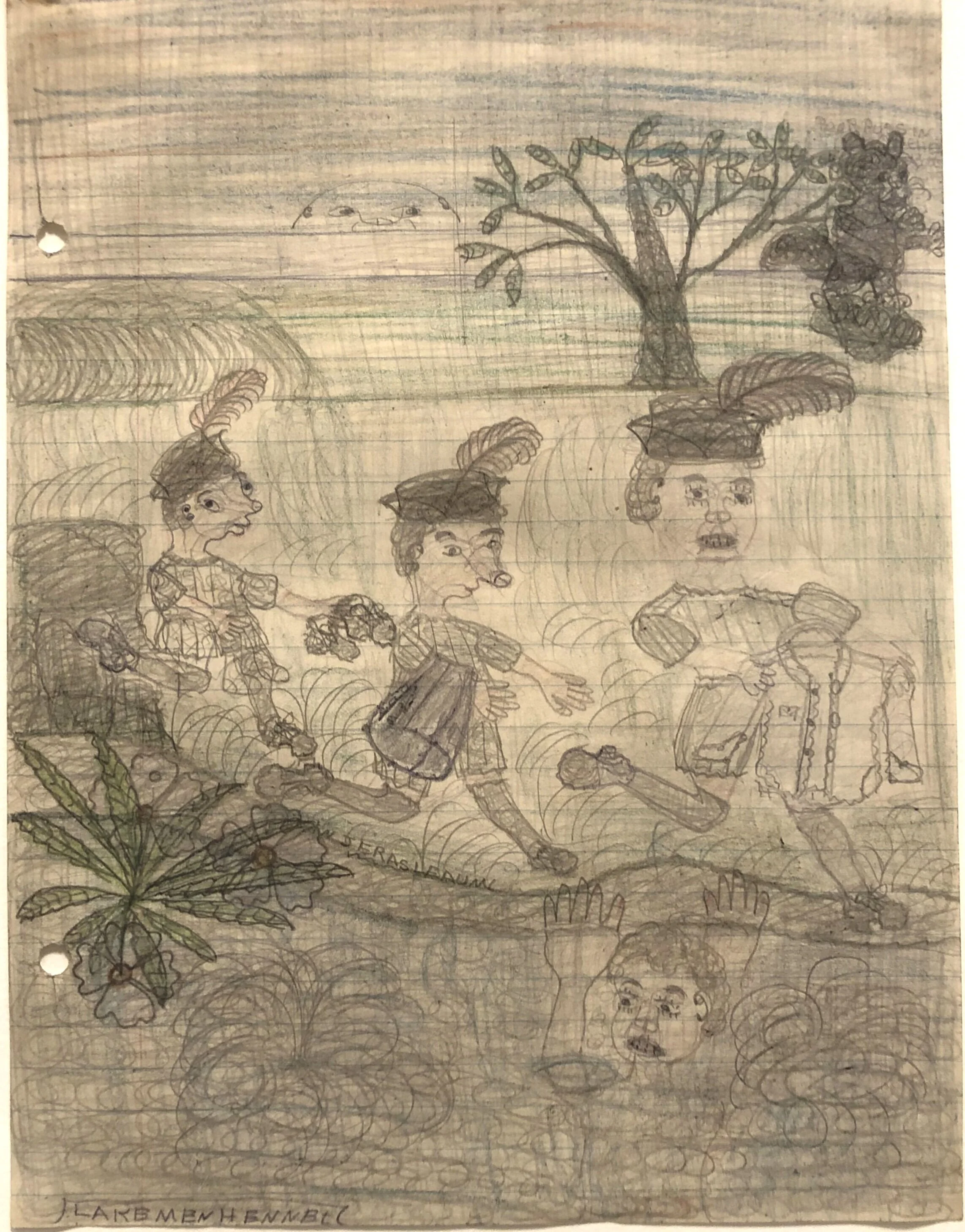

Pearl Blauvelt, Untitled (Lake Menhennel), c. 1940's

Graphite and colored pencil on notebook paper

Blauvelt’s influences might be lost to time, but what is undeniable about these pieces is that they are art and were intended to be so. Their surfaces are covered from edge to edge, and their compositions are deliberate, centered on some sort of action or personage, often labeled (if a bit idiosyncratically).

Unlike the work of Henry Darger—another outsider artist whose prolific output has entered the mainstream—these works don’t tell an overarching story, though the look and feel of her characters remain consistent. Rather, each is a vignette, often referencing places of the Bible, cast as a Pennsylvania landscape.

Perhaps you cannot critique outsider art, but you can feel it. We might have to accept that it says nothing of the grand arc of modernism, but it is an essential piece of the even yet grander story of human creativity. Blauvelt’s work is such an affirmation.

* * *

The sincerity of outsider art (as well as the stories of troves of it unearthed in attics like the discovery of buried treasure) is certainly part of its appeal, but when the art world approaches the work of artists untouched by the establishment, it is wise to proceed slowly.

Celebrate those with innate skill and you run the risk of losing those who have honed it. It is another way of otherizing, essentializing, making female (or black) talent seem like something innate and inhuman, like an alien race of simple, sincere, and powerless people, who need the art world establishment to tell them what they’ve made is capital-A art.

This sentiment has been articulated wisely by the painter Kerry James Marshall, who notes in his forward to a catalogue on Horace Pippin’s work:

“Apparently, for us [black Americans], it seems the less we are engaged intellectually with the art world the better…. How do we, as black artists, acknowledge the genuine accomplishments of self-taught artists like Horace Pippin, without surrendering to routine claims of their superiority over artists who are fully engaged with the theories and practices of modern art making?

[William] Edmondson’s appearance [as the first black artist] at MoMA was no small indignity against Black artists with college degrees who rarely got that kind of notice then or even today.”

How, indeed, do we acknowledge the genuine accomplishments of self-taught artists? One way might be to let them influence us, directly, and without condescension.

Janet Sobel, Pro & Contre, 1941

Oil on board

The narrative of the clueless folk artist is nicely subverted by the story of Janet Sobel, another self-taught artist who is on display in the front galleries of Edlin. Sobel did not begin painting until her 40s, already settled as a housewife in Brooklyn.

Janet Sobel, Untitled, c.1946

Mixed media on cardboard

The painter’s early style, many examples of which are on view in the front gallery, is also naïve, and deeply embedded in the folk imagery of Eastern Europe. (I couldn’t shake seeing the striking resemblance to fellow Eastern European expat Marc Chagall’s lyrical style.)

While the likeness to Chagall’s work keeps it from feeling fresh, we cannot forget that Sobel, of course, is responsible for some of the freshest works art history has ever seen—though many of these paintings were not her making. I’m speaking here of her influence on Jackson Pollock, who saw her drip technique in her studio and brought it to new heights in his own.**

Sobel’s innovation in the context of this show makes an important statement about the mind of the self taught artist, and evidence that the self taught can move rapidly into the mainstream. While certainly it is a stretch to say her creativity, freed from the constriction of a formal artistic education, allowed for such innovation (Lee Krasner, for example, took art classes from her teenage years, and she certainly could innovate!), there is a freedom in frankly acknowledging those without training as a legitimate influence, and seamlessly integrating them into the canon.

Andrew Edlin Gallery

Until February 22

*Of course, the story is more complicated than that, but bear with me for the sake of this review. However, if you must know more, ask me for a copy of my senior thesis about folk art at the fledgling MoMA!

** I am by no means saying that Pollock stole from Sobel—Sobel’s “edge to edge” drip paintings lack the luminescence of Pollock’s and feel much more grounded in the earthly—but he was indebted to her, an acknowledgement he made, but which the art world has happily forgotten.