Women Artists of New England

The artist Sheida Soleimani. Image by Cole Barash.

As a photographer who captures images of elaborate stage-like sets, Sheida Soleimani is engaged with contradictory modes. Photography is a medium whose authenticity we still trust, even after the wide proliferation (and increasing sophistication) of Photoshop. Theater is somewhat of its opposite, allowing an audience to believe in something temporarily, though the delusion is only participated in partly. We are not surprised when we go backstage to see that the set was made of styrofoam and the actors are caked in makeup too gaudy for any normal person to wear on the street. (In fact, a walk around Soleimani’s studio—which includes a library full of styrofoam cutouts, as well as plastic toys, fruits, and other objects—feels not so different from a theater’s own prop closet.)

But it is precisely in this space of contradiction, which exists somewhere between the flatness of her photographs and the depth of her sets, that Soleimani’s work lives comfortably. It is we, the audience, with our social conditioning and media-driven delusions, who are the uncomfortable ones. You see, Soleimani makes art about our own shortcomings and our inability to see what’s in front of us.

Many of Soleimani’s photographs treat the United States, Iran, and the relationship between them as the lens through which she analyzes truth. Soleimani, who was raised in Cincinnati by Iranian parents, has every reason to critique Iran, as the horrors her parents suffered at the hand of the Iranian government are too great to recount here. But neither is the United States above critique. “I’m not neutral in thinking that there is a very whitewashing way of looking at the Middle East from here. But also being Iranian I see the state news media is not allowing any free speech in any shape or form, so I’m also opposed to that.”

She is too astute, however, to think that “good” and “bad” are definite terms and uses her work to ask what it is we mean by such binaries. Take something as simple as the word “prison.” In the black and white terms of morality children are taught to cling to, prison is a bad place, an indication that a person has done something wrong. (White American children are, of course, taught to be unquestioning of the law.) But to a young Soleimani, prison was somewhere familiar to her through family stories, as her mother would often talk of being a political prisoner in Iran.

We can trace a line from these early experiences, which left the artist questioning objective truth, to works like a diptych in which two arms point accusingly at each other, on which two birds—a dove and a hawk—are perched. The dove, of course, is a symbol of peace, while a hawk is positioned at the spetcrum’s other end (as in the expression “warhawk”). The arms, we are told, belong to Donald Trump, former president of the United States, and Hassan Rouhani, the president of Iran. As they are disembodied, we are unsure of whose is whose, despite what the images’ iconography suggests.

Soleimani’s work is a cacophony of imagery—it is often difficult to parse what is happening within them. Their jumble doesn’t yield a clear narrative, but a neat story isn’t what she’s after. “It’s a sense of archiving for me. Archivability, history, tracing, tracking things down. When we’re in an image saturated economy these things are inundating us all the time. How do we sift or navigate through them? Often times we don’t.”

Soleimani’s words suggest that we are actually less visually literate than we might once have been. It proposes a new understanding of “fake news,” not as lies, its fakery embedded in the content, but rather in the way fact is presented. The flimsiness of the news might be derived from the surfaceness of it, our inability to glean complexity from the sheer amount we consume. It’s not fake, perhaps, but it is flat. This relates to the apparent flatness of Soleimani’s photographs (taken with a high aperture to produce such an effect) which, when viewed from the side, are a riot of dimensions.

Though many first think her photographs are elaborate photoshopped collages, the viewer eventually understands—thanks to shadows and other markers of depth—that what we’re looking at is a photograph of three dimensional space. The intense desire to move around the scene, however, quickly yields to frustration in realizing we are unable to see more of what is in front of us. We are stripped of the tools we’re accustomed to using in order to seek objective truth.

A single perspective provides no nuance, and that is precisely the point.

More on Sheida here.

LUCY MINK

Contoocook, New Hampshire

Though the language of any great abstractionist is recognizable through her use of color—the dusty pink of Hilma af Klint, for example, or the watery pastels of Helen Frankenthaler—all aspects of her brushwork express a vision. A good abstract artist will have a style as unique as handwriting.

The artist Lucy Mink.

For New Hampshire-based Lucy Mink, mustard yellow often appears in her abstract paintings, but during the pandemic she has tried to change it up. “I always go to the favorites. I love certain things,” she admits, but when her son pointed out how many paints she never uses, she was inspired to reach for the colors that she had been neglecting. “I might find something in one of those tubes of paint that is great!” she says, thrilling at the potential. But color is not what makes a Lucy Mink painting a Lucy Mink painting.

It turns out that the first choice she makes—whether that knee jerk impulse to embrace comfort or a desire for the opposite—determines a lot about the outcome of the painting, as Mink does not begin with an idea of what she hopes it will look like, a sentiment she also applies to her career. “I want to be surprised,” she says, “I don’t want to know what I’m going to make in five years. I'm never stuck in one thing, even though my work always looks like my work.”

But why does her work always look like her work?

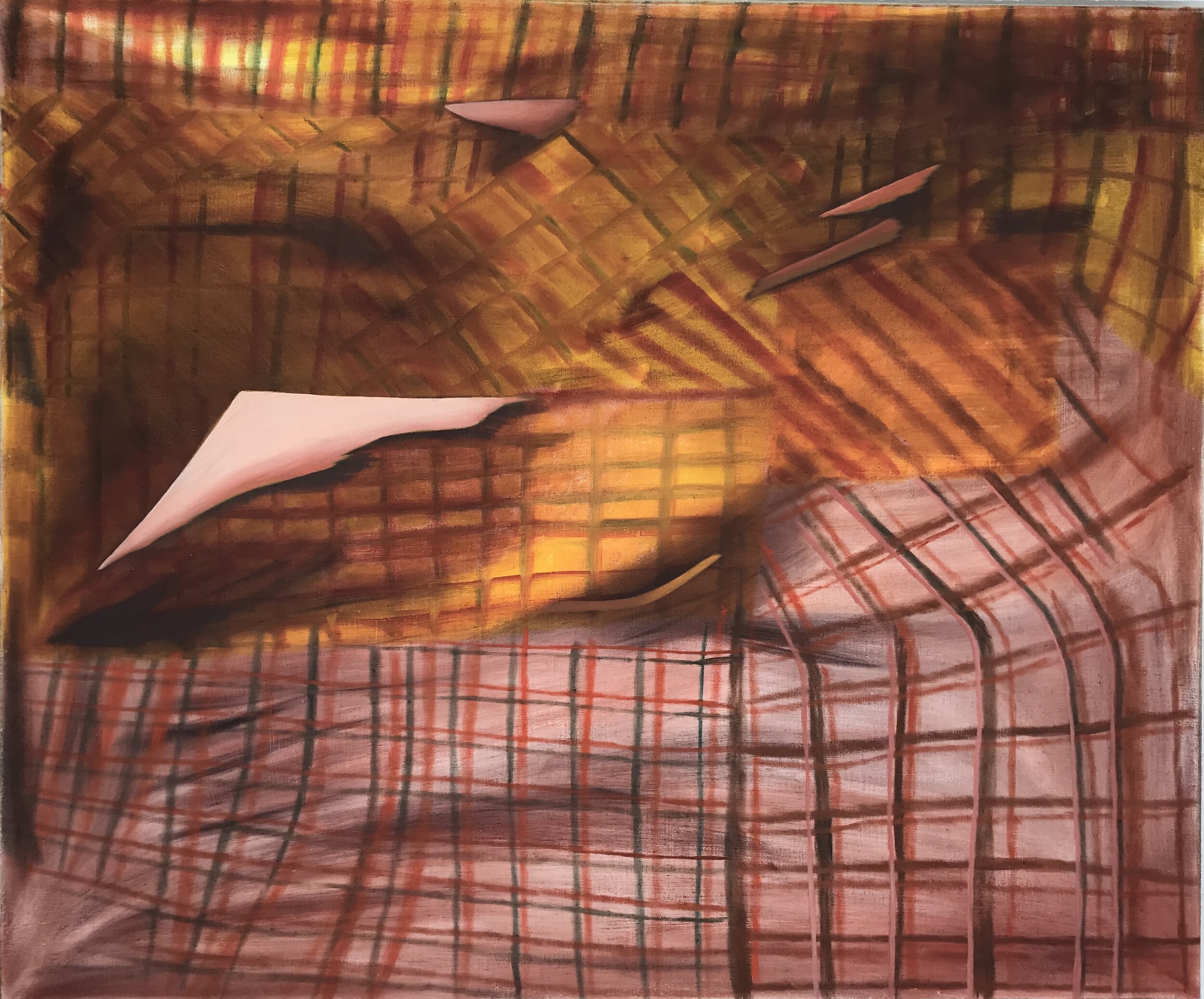

“Near Us” Oil on linen. 20 x 24in.

Is it the feathery strokes that appear across her paintings? Sometimes these flecks feel corporeal, like striated muscle, sometimes like fur or hair, though at other times they call to mind the early abstractions of Georgia O’Keeffe. Sublime transcendence of an O’Keeffe variety, however, doesn’t seem to be what Mink is after, as her patterned shapes rarely feel as if they point to space beyond them, suggesting neither width nor depth.

Perhaps what makes a Mink a Mink is a sensibility that can also be found in the works of the other (mostly figurative) painters to which Mink referred throughout our conversation. Her evocation of David Hockney had particular resonance for me, as Hockney seizes on patterns to be found in his domestic scenes and landscapes and abstracts them into smooth, bright surfaces. (Take, for example, the squiggly water in his iconic California swimming pools.) This flattening strikes me as the inverse of what Mink does—taking patterns and giving them the passive, but fully present warmth a plaid blanket might have when lying over the back of an armchair.

While there’s something deeply causal about Mink, it is not in that California way. If nothing else, New Hampshire—where she has lived for 10 years—affords her the space to rework what doesn’t sit well with her and, sometimes, to wipe it all down and start again. “I’m not in a rush to finish the next five paintings fast because I don’t want to have those decisions be made too quickly,” she says. And while she doesn’t know exactly what makes a painting not work, she knows it when she sees it.

Willingly choosing not to look five steps ahead in a painting is not the same as being blind to even the next step, something the uncertainty of the pandemic ensured. “I had a painting go so badly in March and April that I took it off the stretcher. I thought, you know what, I’m done,” she says with finality. To get back to a state in which she could paint amidst national chaos, she found ways to let her muscle memory do the work by distracting herself with a phone call while she painted.

There is certainly a Surrealist sensibility in letting the mind take over, but instead of revealing Oedipal experiences and long forgotten traumas, Mink’s “surrealism” opens up into a space of form responding to form. The ping pong nature of her process (starting one painting, leaving it, using the same motif to start another painting) feels more like an exercise in fate than as a means to map out the human mind. What is the result, the artist seems to ask, if the inputs are changed? How can we start in the same place and end up so far apart? Her paintings seem to visualize these journeys—as if she painted a conversation, a formal log of the back and forth between artist and her object.

So what makes a Lucy Mink painting what it is? The same thing that makes each of your conversations unique, but uniquely your own.

More on Lucy here.

Lynne Allen

Boston, Massachusetts

The artist Lynne Allen

Most people’s family archives—pages curling, stuffed in shoeboxes, or else sitting in a basement filing cabinet—are not of interest to many beyond those who’ve inherited them. But when Lynne Allen was given her great-grandmother’s writing (which her ancestor had hoped to publish in her lifetime, but never could), she was in possession of more than the stuff of a family reunion’s show-and-tell: she had inherited her people’s history.

Allen’s ancestor was Josephine Waggoner, a member of the Hunkpapa tribe of the Lakotas, and a chronicler of Indian life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Seeing her culture rapidly disappearing around her (she herself was sent to be educated at the Hampton Institute, a boarding school meant to assimilate freed slaves into white American life), Waggoner set out to put it down on paper, interviewing tribal leaders and even meticulously copying down the tribe’s “winter counts,” or the traditional form of recording events among the Sioux.

Wind Woman, digital print relief, woodcut, 17 x 17.

Though the journals were published by the University of Nebraska Press in 2013 (an accomplishment four generations in the making!), the life of the documents is still growing and evolving in the hands of Allen herself, who uses her ancestor’s words—and handwriting, which the artist has learned to flawlessly reproduce—to inform her body of prints. Certainly these documents are an invaluable piece of the history of the Lakota people, as well as our own nation’s, but they are also essential to Allen as an individual and to her own relationship with her matrilineal forebears, all of whom lived on the Standing Rock reservation. (Allen herself is not, however, an enrolled member.) “In my native culture everything is passed down by the women,” she explains, “there’s something about knowing that those women cared enough to pass that down. I don’t want to say it makes me feel special, but it makes me feel a part of something.”

New World Order. (2019) 27" x 34", etching.

Much of her work asks her viewer to recognize the part they play and to extend their consciousness to encompass something beyond themselves, even if the subjects of many of her prints fail to do so. In New World Order, under the looming shadow of mountains two people blithely sit in a speed boat, which rips across a body of water the size of a bird bath. This print, ominous in its dark cast, warns us of the danger lurking at the edges of our nonchalance regarding climate change, as well as nature’s inevitable indifference to our species’ survival. Allen is a Tamarind Institute master printer, and her dexterity with the medium is clear throughout her oeuvre, in this and other prints.

Endangered. Etching and woodcut, 14.75" x 20."

Many prints use the metaphor of the extinction and endangerment of species as a way of demanding we consider the bigger picture. They are not just premonitions of the future, however. In Facing Extinction, for example, the depth of the print connotes a sequence of events that elegantly describes the circuity of history. In the foreground stand a hyena and a badger—both endangered species—about to square off (the hyena is stepping forward with its hackles raised), indicating an imminent action. Behind them, an animal pelt hangs in undefined space, perhaps foreshadowing the death of the two animals. The background of the print’s upper portion is covered in a facsimile of Allen’s great-grandmother’s writings, drawing a parallel between the animal’s own endangerment with the loss of Native populations (and their history) due to “white colonization, disease, poverty, marginalization, an altering of a way of life, religious beliefs, everything.” In other words, “man’s inhumanity to man.”

Facing Extinction. Etching and woodcut chine collé, 19" x 21", 2019.

However, the pelt, a symbol of the possible extinction of these animals, hangs in the same space as the handwriting, which harkens to the past. This commingling of past and future suggests that time does not move linearly, but rather repeats itself. The animals fight and die, their pelts are mounted as trophies, and the story foretells their death. The progression of human history is a cycle that without interruption will repeat its violence. This call for intervention is what lies at the heart of Allen’s work. “That’s what drives me and has always driven me. It’s my empathy for life,” she says.

Josephine Waggoner wrote her people’s history. With her great-grandmother’s words as a guide, Lynne Allen fights to preserve a future in which her ancestor’s past—indeed, all our pasts—can still be appreciated.

More on Lynne here.

Deborah Wing-Sproul

Portland, Maine

The artist Deborah Wing-Sproul

While performance is “just one leg of the stool” in Deborah Wing-Sproul’s artistic practice, there is something essential about the body’s centrality to the medium that explains much of the rest of her practice. As a young woman, Wing-Sproul was a dancer, trained in the Cunningham technique, which she quickly took to (“I was 100% a dance junkie,” she says of her former self). Something about the discipline, however, wasn’t quite right. “I didn’t feel I could get to all of my ideas through dance,” she recounts, so Wing-Sproul left the medium behind in favor of video. It wasn’t until years later, however, that she began to refocus on her body, though this time as the site of perception, rather than a tool for technique. The relatability of the body—“We all have a body,” she explains—governed this work. “We have bodies that can do more or less or in different ways or with greater or lesser pain or difficulty. We experience everything with these things we carry around.”

Some of Wing-Sproul’s projects center around corporeal sympathy, while others are meant to wake us up to the confines of our own flesh. But in order for Wing-Sproul to guide us into waking up to ourselves, she requires one thing: that we pay attention. “The difference between art and entertainment is making an effort,” she notes, “It’s not passive.” Being present for even two hours—such as is asked of the audience for the artist’s Durational Devices performances—seems a small price to pay for what results: a better understanding of what it means to be human.

If this seems like a lofty claim to make of a single piece of artwork, it might be because reading about it evokes a pale imitation of its power. Long durational performance art asks you to commit to witnessing the limits of the body, and in doing so feel your own (an effect, unfortunately, which my writing has yet to produce). It asks you to confront directly the things from which we too often look away. After attending the July 2018 performance of Durational Devices III, the writer and art historian Nancy Princenthal shared her experiences in a public discussion with Wing-Sproul: “We’re watching somebody do something that’s actually very challenging physically. And we’re bearing witness to somebody doing something difficult, even painful,” she explained, “These Durational Device performances engage us in an exploration of what that difference is.”

Durational Devices is a series of two-hour performances in which Wing-Sproul positions herself on five unique wheeled platforms each performed with their own drawing device, on which the artist remains in a single position, propelled only by her toes. The performances are difficult for the artist, both mentally and physically. “What happens is that I lose control of my body. The muscles are seizing up.” Her pain, however, is essential to the piece. “We have a proclivity to turn away from people who are old. People who are homeless. People who are injured. Because it’s difficult to take in,” she says. “As human beings, maybe particularly as Americans, we compartmentalize our experiences to a degree that’s truly sociopathic.” To fully experience the privilege we have, but also to fully experience our own pain, we must find a “feedback loop,” which pushes against our now embedded inclination to turn away. Much of Wing-Sproul’s work is an introduction to finding that mechanism and flexing that muscle so that in times of joy we can see the depths from which we have risen and in times of despair we can glimpse hope.

She likens the loop to “travel brain,” that mental state which sets in when in a foreign place, where we might not speak the language and are perhaps susceptible to danger in a way that we are not at home. Her latest work, which was born out of the state of vulnerability brought on by the pandemic, simulates that mental stance. In an installation of photographs and sculpture we are meant to question the precarity of comfort, as well as human frailty.

The installation features four photographs—the first an image of three pools of bright blue water, still and tranquil. In the second image, one of the pools has been emptied, the concrete box used as a fire pit. In the third, there is evidence of someone having used one of the boxes as a wash basin. “Most of us have walked down the street where there’s evidence of someone having done something. Eaten something, burned something, taken care of their body,” Wing-Sproul explains. In the fourth, the pools have become a resting place. The four images, almost a timeline, evoke that sense of human presence, but in a more sinister way. Though we are glimpsing traces of life in the photographs, there is a fifth element of the installation: a sculpture at the center of the room. Laid across the actual pools on shards of wood is a sheet, as if a shroud covering a body. The threat of something is palpable, though it is unseen.

How are we to interpret the fear the installation calls forth in us? Are we to believe we are next? Or are we already the body beneath the sheet?

Neither, it turns out, and maybe the opposite. “I trust uncertainty more than I trust comfort. When we’re not certain about something it keeps us honest,” Wing-Sproul says, and what’s most important, “it keeps us alive.”

More on Deborah here.