Women Artists of Texas

The artist Liss LaFleur

I’d love for someone to make a video game out of media artist Liss LaFleur’s “Future Feminist Lab,” a course she teaches at the University of North Texas in Denton, where she is Assistant Professor of Studio Art. At the end of the semester, LaFleur asks students to design a feminist utopia (after doing a sizable amount of reading up on the history of feminist art and philosophy) by reimagining the systems we live in in ways that would serve women. There are so many games that have world building at their core—most with a self-serving end like amassing wealth or building a gargantuan house—so why not make one that seeks to build a better world?

“I’m interested in Future Feminist discourse as an artistic practice and in it as a pedagogy, one of the rare places that [my roles] as a professor and as an artist has overlap,” LaFleur says, and she certainly practices what she preaches by using technology to give visibility to the marginalized, such as through her digital stained glass homage to the rioters at Stonewall. She recognizes, however, that “tech facilitates the practice but...also has a lot of inherent biases.” Living in this world, rife with structures built for men, she must work within the confines of a system that does not conform to the world she has built in her Feminist Lab.

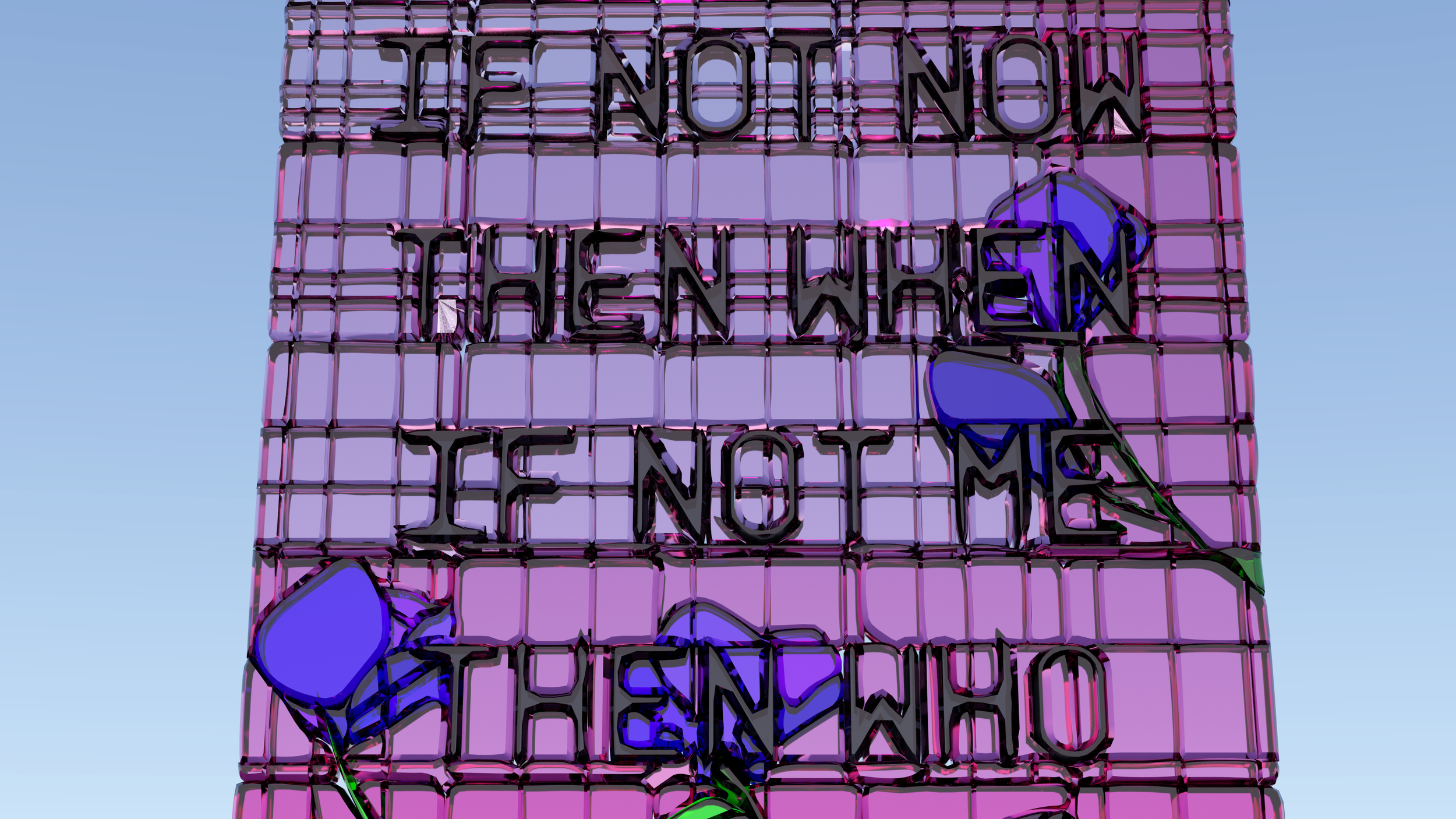

In Coded Glass, for example, LaFleur constructs feminist protest signs out of digital stained glass, using language mined from Twitter. While certainly a work about feminism and women's rights, the artist also uses it to address the ways in which for-profit websites exploit their female users by selling their data (and therefore, their stories). For this project, the artist needed access to information hosted on these websites, specifically the data pertaining to the use of the hashtag #metoo. To acquire this data, however, LaFleur needed to work around the proprietary nature of companies like Twitter and Facebook, who tried to charge the artist tens of thousands of dollars for a single month’s worth of content, in an attempt to capitalize off of the pain of millions of women. Recognizing the abusiveness of this request, the artist went on a “punk style, renegade data collection” spree to acquire the necessary information.

Coded Glass, 2018

As a self-described “dyke in Texas,” LaFleur is also contending with a system of homophobia and hostility in a culture notorious for its conservative close-mindedness. This system, conversely, she does not work around, but rather uses to her advantage. “It makes me want to push harder to live in a place that is oppressive [and] isolating,” she says. In a recent press release, she put it more starkly, stating: “As a queer woman in the south, guns are often considered normal and accepted more than my own body and existence.” (She has been known to include guns in her work, always in a tongue-in-cheek fashion.)

Peeshooter. Still from performance.

Female urination device and pored resin pistol

2017

Normalcy, however, takes a nose dive in LaFleur’s latest project, which centers around a single document declassified by the Canadian government, which alludes to the existence of the “Fruit Machine,” a series of tests designed to rout out homosexuality from the army and civil service. If feminist fantasies of the future seem farfetched, this document is the stuff of Hollywood movies: among the ways to identify someone as gay was a sweat test, in which subjects held crystals in their hands to induce perspiration. The results from this and other pseudo-scientific trials were meant to determine the subjects’ sexuality.

In an artist workshop, LaFleur tasked the participants with reimagining this “machine” (by now this reinvention should feel like a familiar element of her pedagogy), as the details of the original are shrouded in mystery. One of her own interpretations comes in the form of a twenty minute video, Boi with Fruit Basket, which features a clinical voiceover reading from some of the document, as we watch a woman systematically eat fruit from a bowl, as if under observation. The subject’s frank, direct gaze as she works to eat the basket seems to be in defiance of the machine’s categorizations, a challenge to its attempts to define her. The video plays upon the euphemism “fruit” to describe a gay person, but also references a painting by Caravaggio, who himself is considered to have been gay, as if to say it’s impossible to expel queerness from our culture, and what’s more, what would art be without it?

Still from Boi with a Fruit Basket

Single-channel HD video (20:00 min.)

2019

When I asked LaFleur how this retroactive redesign related to her ideas of Future Feminism, she responded simply: “it’s the same.” The irony is that if you can design an object of prejudice, bullying, and persecution, you can design its opposite. Sometimes to see a utopic future, you must be intimately familiar with the worst of the past.

As they were so familiar with the patterns of the “homosexual,” my “what if” mind cannot help but think, what if the designers of the Fruit Machine had decided instead to build a haven for the people it was determined to identify? Unfortunately art cannot rewrite history, so we’ll have to settle for the video game version of that unrealized past.

More on Liss here.

Tamara Johnson

Dallas, Texas

Tamara Johnson already had experience exhibiting socially distanced art before the pandemic began, though that’s not exactly what she called it. In January and February at Dallas’s Sweet Pass Sculpture Park, which the artist founded with her husband in 2018, the park is closed, though the pair keeps a sign on the gate urging visitors to tune their radios to FM 96.1, a channel on which the pair have curated an “exhibit” of sound art.

The artist Tamara Johnson

In order to open the park, Johnson moved back to her native Texas from New York City. Throughout the eight years she lived on the East Coast, however, Texas was never far from her mind, nor her art. The foreign landscape of New York—its cracked sidewalks and unconcerned attitudes toward outdoor space—was where the language of her work found articulation in objects like the garden hose and picket fence, nostalgically familiar for Johnson, but laden with meaning for the New Yorkers who find them only in their dreams of one day decamping to Suburbia.

Water hose, Live Strong, 2016. Components of solo exhibition, No Your Boundaries, presented by CUE Art Foundation, New York, NY, Rope, rubber, aluminum, plastic, pigment, oil-based paint, 70in x 26in x 40in

Photo by: Phoebe Streblow

Memory and distance (and an artist’s mind), however, have a way of warping objects into symbols, leaving Johnson’s hoses loopy and her lawns animate. For No Your Boundaries, an exhibition at the CUE Art Foundation in 2016, she remade the classic outdoor water hose—the plaything of choice for frolicking summer children—from rope, which she coated in vibrantly colored silicone rubber like the textured surface of a cake. In red, green, and yellow, they loop themselves into curlicues with the joy of letters written in icing.

Joy, and its frequent companion, humor, propel Wandering Yard (2013), a work in which Johnson placed a square of grass sod atop a remote controlled car, which you can watch wander around the city looking for a lawn to call home, lost, yet hopeful in its childish whirring apparatus. Elsewhere, the same contraption was installed in a gallery space, where it banged itself repeatedly into a wall until its battery gave out, again out of place and confused at being confined to the sterility of the white cube. Its avatar was present in the same exhibition, in the form of a sculpture of an armadillo, folded in on itself out of fear and anxiety.

Armadillo, 2016. Component of solo exhibition, No Your Boundaries, presented by CUE Art Foundation, New York, NY. Hydrocal gypsum, oil-based paint. 5.5in x 5.5in x 6in.

Image courtesy of Artist

Many of these metaphors were personal for the artist: “I always sort of felt like [that] in New York, like a curled up armadillo, protecting the soft interior,” she admits. You might imagine, then, that the armadillo that was Johnson might have been shocked to uncurl and find herself back under wide open Texas skies. What becomes of you when you can no longer define yourself against the place you inhabit? Is Johnson’s vocabulary of backyards and swimming pools no longer usable? Or does it shift, allowing her the freedom to speak for herself, rather than where she comes from?

To be an ambassador artist can be exhausting— to be always explaining yourself doesn’t leave much room for personal development. Being back home, however, the artist has changed tacks: “A lot of the things I’ve been working on and making now are less about the landscape of a place, and more my own interior landscape,” she says, “Now I've gone to the other side and am thinking about my identity as a woman in Texas, growing up in the South.”

Backyard Pool, 2014. Commissioned by Socrates Sculpture Park and Rock Rose Development Corporation. The Lot, Long Island City, NY. Concrete, ceramic tile, aluminum, fiberglass, seed, acrylic paint. 26in x 44ft x 27ft

Images courtesy of Artist

My personal favorite result of this inward turn is the artist’s version of Brâncuși’s Endless Column, in which she cheekily pokes fun at male artists’ obsession with their phalluses by making what I think of as the Southern Potluck Endless Column, a repeated sequence of resin-cast pickled okra and deviled eggs (complete with paprika). In the piece (which in reality is called Deviled Egg and Okra Column), she sexualizes 1950s Texas housewifery by alluding to penetration, repeatedly— almost obsessively—joining phallic okra with the ovum of deviled egg. To me, the work alludes to what is always just below the surface of Southern hospitality: something much more complex, much more human than a social function might initially imply, appearances that I believe women particularly are tasked with upholding.

The column is made to measure—its individual widgets screw together (another allusion to sex?), allowing it to stretch to fit wherever it needs to be. The artist even has ambitions to cast it in bronze, in which case it would go “all the way up to the sky,” just as Brâncuși’s does, but this one a monument to Texas’s women.

Deviled Egg and Okra Column, 2020. Part of Nasher Sculpture Center’s Nasher Windows. Resin, aluminum, oil-based paint. 16ft x 2in x 2.5in.

Photo by: Kevin Todora

“Where my work is [concerned] I try to make it integrated into the space as much as I can... I still take into consideration the scale and the dimensions and the neighborhood and the architecture because to me if I can find a way to tap into the intrinsic value of a place, then that situates the work in a way that feels not like it’s just placed.”

I don’t know about you, but it sounds like she might also be talking about herself. In order for Tamara Johnson to find meaning, neither place nor home is incidental.

More on Tamara here.

Paloma Mayorga

Austin, Texas

The artist Paloma Mayorga

There’s an astonishing amount of depth in multi-disciplinary artist Paloma Mayorga’s work, a remarkable achievement given the original function of her tools. Mayorga takes photographs with a scanner—a machine that is meant to reproduce what is on its glass and nothing more, and yet in the artist's hands it is capable of creating lush worlds, teeming with plant life and filled with mystery.

Perhaps it is in the contrast between surface and vacuum, the way the technology of the scanner depends on reflection, that makes her work so rich. Mayorga keeps the machine’s lid open when she works, placing leaves, petals, flowers and other plants she has collected on the scanner bed. In the places where the plants are not, the scanner’s bright light has nothing to bounce off of, so its rays simply “keep going,” leaving absence in their place, an inky black background as cold and empty as space.

The results Mayorga achieves are not limited to this binary, however, as she plays with the effects of proximity and movement. When she drags her hand along the glass, she is “able to get these elongated forms that almost come out like paint strokes,” she notes. Her earthy colors, too, evoke painting, as well as a long tradition of still lifes situated on dark grounds.

Su dulce miel (Her sweet honey), 2013

Digital Photography

Mayorga’s comparing her results to painting is unsurprising, given her background in the medium, but she admits that that is where the similarities end: “This is a very different way of thinking [from painting] because I am putting things on a scanner bed, but the image is...taken from beneath.” In other words, the final image you see here is the inverse of what the artist saw from her vantage above the composition.

tócame/no me toques (touch me/touch me not), 2019.

Photo transfer on gelatin

2” x 3”

This reverse construction is not altogether foreign to the history of art, though Mayorga’s process is certainly unusual in this millenium. Glass painting is a centuries old technique in which canvas is replaced by glass, with the intention of displaying the painting glass side out (therefore demanding details, rather than background, be painted first). The painting’s progress can be monitored as the artist works by simply flipping the glass. Mayorga, however, is “not seeing the image before it's scanned. I’m creating an image based on what I think it might be,” she says.

It is unusual that the artist cannot see what she’s photographing, as photography is fundamentally observational: it mimics the mechanism of sight by relying on light reflecting off objects to create an image. If Mayorga can’t see the image before it’s printed, then who does?

The answer, in this case, is the machine. In thinking about her photographs, I became fascinated with the idea of this second consciousness, seeing her work before the artist can glimpse it. We, as the viewers, then, are a proxy for this technological observer, which perhaps accounts for the strangeness I feel when looking at these works. Sometimes they feel as if I am looking into space, sometimes into a deep pool, a pond with a sprite trapped beneath the surface, tangled with the reeds. No matter how I interpret the work, however, I always feel as if someone is beside me, looking with me.

Muerdo (I bite), 2013.

Digital Photography

Mayorga occasionally plays into this in a few of her images, in which she seems to be referencing something beyond the frame. In one, jaw bones are surrounded by a circle of petals, a ritualistic image even if we do not know to what it refers. In another, words are etched into the surface of an aloe leaf, “la cortas y ella se sana con su dulce miel [you cut her and she heals herself with her sweet honey]” an ambiguous message that could refer to either the plant or an unspecified woman. But these types of references are anomalies: most images are of plants and fingers (with the occasional ear or breast), pressed against the glass.

tócame/no me toques (touch me/touch me not), 2019.

Photo transfer on gelatin

2” x 3”

This “specimen aesthetic” is particularly pronounced in her newer work, in which the artist uses an ingenious combination of material to create small translucent objects, almost like microscope slides. Using sheets of glass, Mayorga transfers excerpts of her photographs onto gelatin with temporary tattoo paper. She is most interested in where her “fingers are messing with something,” as she liked the idea of “tak[ing] those tiny moments and somehow putting them back on my own skin.” The tattoo paper, which functions as if a second skin, was perfect for that job.

These works are especially interesting when they shrivel like aging skin. Though their substrate mimics scientific slides, whose intention is to preserve, these works admit to a different reality: one in which life decays and the moment passes. Together these bodies of work—one pausing to dwell on the bloom of life, the other embodying its demise—represent the fullness of life’s cycle.

More on Paloma here.

Ariel René Jackson

Austin, Texas

The artist Ariel René Jackson

If I could say Ariel René Jackson’s art practice is about something, I’d say it’s about revelation, but not the kind where the skies open up and a beam of light shines down, but the type of revelation in which the human body wakes up to its realities—the accumulation of data, experience, and stories that amount to knowledge.

“Even if you don’t understand the facts of what’s going on, there’s other ways of knowing that things are fucked up,” Jackson says. “I have known in my body where I’m not welcome and where is hostile.” Jackson grew up in New Orleans and spent seven years in New York City, both places with their fair share of hostility towards Black people, though they express it in different ways.

Jackson has lived in Austin for the past three years—two of which were spent in a graduate program at UT Austin. She makes it clear that despite the perception of Austin being a liberal bubble in a red state, the city is interested in preserving a specific type of open mindedness: that is, one that belongs to whiteness.

It took her a while to understand that gut feeling however, so when a friend visited and immediately perceived it, she “felt foolish” because it had taken her several years to get to the same conclusion. No matter though, as the methods in which she makes conclusions are the subject of much of her art practice.

How does this complexity, this slow dawning manifest in physical work? It might not surprise you that Jackson most often uses video, a time-based medium, to communicate what she has to say. “I’m interested in the possibilities of video to be a tool for showcasing a reality that is felt.... I love in-camera editing,” the artist explains.

The future is a constant wake, 2019.

Film still courtesy of Ariel René Jackson

She often uses the word “forecast” in relation to her work and employs the use of the symbols associated with that word in her videos. Among these objects is the weather balloon, which collects data about the atmosphere which scientists can later analyze to form conclusions.

The balloon appears in her video Bentonville Forecast: In the Square, in which the artist interviews Black women in the town of Bentonville, Arkansas, a place “trying to be a liberal bubble... trying to convince Black and Brown people to move there” despite the fact that there is a Confederate statue in the middle of town. In voiceover, one woman describes avoiding the square in which the monument is located. Another talks of thinking about it the moment she steps out the door, as if the very air is saturated with this hatefulness—the levels of which, perhaps, a weather balloon could measure.

Bentonville forecast: in the square, 2019.

Video still courtesy of Ariel René Jackson

In the video Jackson stands with the balloon in front of the statue. The way the camera is angled, the black balloon bobs in front of the soldier’s head, metaphorically foregrounding the reception of the statue, rather than the monument itself and insisting the former is what we ought to pay attention to.

Jackson acknowledges that there is a quick diagnosis for places like Bentonville, which are able to hold this contradiction within them: “It’s racism is what it is. It’s gentrification is what it is,” she states, but she also acknowledges that these pronouncements are not always helpful. “I think art allows for the possibility of breaking that language,” she says. Art can get at what’s really going on, what it feels like to be on the receiving end of a racist culture.

Take Its Extended Remnant, in which Jackson applies chalk to a blackboard with a rusted tool that once belonged to her grandmother. When she wipes away the chalk, its residue gets trapped in the grooves of what was always there, but that we could not perceive: an engraving of Senegalese woman in a rice field from Judith Carney's book Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas (2001). She covers it again, this time with dirt, and then methodically dusts it off with a paintbrush, like she is performing an archeology of culture. This is what Jackson means when she talks about “creat[ing] a structure of how to get to know a place.” The deliberate process of applying chalk and soil was necessary to uncover a deeper truth lurking beneath the surface.

Its extended remnant, 2018.

Film still courtesy of Ariel René Jackson

“I think that science comes out of culture. I’m trying to make that argument by marrying convoluted language that when expressed it… seems more intuitive than it is prescriptive, although it is coming from a philosophy, a stance,” Jackson explains. In its slow reveal, narrated in steps almost like a recipe, Its Extended Remnant does just that.

These days, Jackson is preparing for her solo show at Austin’s Women and Their Work gallery, which is set to open next year. It is important to her that the show be in the city she has spent the last few years understanding. “This show will be for the very few Black folks in Austin,” she says, as if she means for it to help them absorb a different attitude from the city, one which embraces their presence.

The future is always a “balance of hope and fear,” Jackson insists. The artist’s show, fleeting in its presentation, is not going to change Austin. But it might change its mood, and that’s really what she’s after.

More on Ariel here.

SEE ALSO: less than half’s March 2020 profile of Houston-based video artist Virginia Lee Montgomery.