Women Artists of the Gulf Coast

Skip to: Linda Lopez, Ida Floreak, Phoenix Savage

The artist Amy Pleasant

Amy Pleasant

Birmingham, Alabama

In college, a close friend pointed out that I touched my face a lot. Not just touched it, but used the tips of my fingers to press and massage my cheekbones, from the top of my nose to the tips of my ears. As when anyone holds a mirror up to you, I was shocked—I had never noticed this before, but of course it was true: when she mentioned it, I could feel the gesture in my bones. It was a private tic, something I only do when among friends. To have it recognized was an affirmation of our closeness.

I’ve written about gesture and body language in art before, in the context of figuration as well as abstraction, but for the artist Amy Pleasant, whose silhouetted language of pose is a signature, it is a signifier of an individual’s environment rather than the individual him or herself. (Pleasant is careful not to betray gender in her figures, unless she expressly means to.) She zeroes in on “the zoom in, the crop, the moment,” and transforms each into a kind of graphic warmth meant to evoke casualness, intimacy, and comfort.

Unsurprisingly, writing and other succinct visual forms of communication such as hieroglyphics, calligraphy, and cuneiform are all sources of inspiration. (Pleasant nods to this by using her figures as letters on the cover of her latest book.) While the lack of color might seem to evoke the black paper of silhouetting, she arrived at it from the immediacy of india ink, which she uses to make her swift line drawings in the same way you might dash off a note. Each drawing is slightly different from the next, as personal as handwriting.

As One Knee Bends to the Ground | 2019 | ink and gouache on paper | 25 x 40 in

The gesture the artist holds in her body while making these drawings is key to their success. Body language is, of course, reactionary. We tense up when others do, we mirror body language as an act of empathy. “Single motion drawing is really important to me,” she says, “It’s directly connected to being present. Present in my body, present while I’m drawing,” adding “breathing has become a really important thing to me. Being present. Staying calm.”

To get the same immediacy in paint she lays the canvas on the ground in much the same way her abstract expressionist foremothers would have (I’m thinking here of Helen Frankenthaler). Though Pleasant paints figuratively, the similarity of process begets similar results: the immediacy of both abstract and figurative marks are meant to evoke something viscerally emotional.

Legs | 2014 | ink on paper | 22 x 22.5 in

Pleasant uses repetition to make what is small monumental. “All the repetitive things we do every day which we don’t think about” make it onto her canvas in replicated forms, though each differs from its neighbor. Among these gestures is that moment “when you’re sitting in a chair and you become aware of your own self,” something we might not give much thought to otherwise.

Of course, this personal observation is a lot more common these days, when it feels as if we’ve never spent more time with ourselves. The intimacy of touch and gesture (like the one my friend pointed out), too, are missing. The significance of these images has only been heightened in quarantine, when our exposure to others has been so severely curtailed.

Prop I and Prop II | 2016 | ink and gouache on paper | 22.5 x 30.25 in (each)

I can’t help relating Pleasant’s work to another of this summer’s great reckonings: our country’s confrontation with its long history of racism and discrimination. As Pleasant works in Birmingham (the city in which she was born and raised), I asked her about the removal of the city’s Confederate monument, which the mayor took down despite the threat of legal retaliation from the state government. (“It was exhilarating to see the statue removed in the middle of the night,” Pleasant said, praising the mayor’s actions.) In many ways these public monuments represent the opposite of the work in which Pleasant engages. Not only are the gestures and stances of these sculptures’ subjects an assumed posture of triumph and heroism, which belie the causes and the outcomes of the Civil War, but the effect which they have is also unnatural. The body's reflexive response to danger is tension, and our limbs move and are held in ways that are visibly uncomfortable when faced with stress. The effect these monuments have on their citizens is often one of discomfort and pain, manifested in the body’s movement.

In this context of social unrest, Pleasant’s paintings are aspirational markers. After all, spaces in which we are able to physically reveal ourselves are successful spaces, where community is more likely to flourish. Pleasant’s work reminds us that it is a privilege to behold the intimate gestures of another, as comfort is something we cannot fake. We earn it with others by being good friends, with our communities by being good neighbors, and with ourselves by learning, amidst so much chaos, how to breath.

More on Amy here.

Linda Lopez

Fayetteville, Arkansas

The artist Linda Lopez

Using the materials of our physical world, artists translate their experience into form. For the artist Linda Lopez, art is a window into her childhood and serves as a clue to the way in which she creatively woke up to the world. All children have an imagination, but few more so than Lopez, who grew up in the United States, the daughter of a Mexican father and a Vietnamese mother.

Neither parent spoke English with fluency, so where language failed creativity stepped in. As her mother was frequently guilty of what Lopez has retroactively labeled “pathetic fallacy,” or our tendency to assign human emotions to the inanimate, she learned of the spirit of objects alongside their physical existences. “Don’t get crumbs on the couch—you’ll make it sick,” her mother would say. To a young Lopez, furniture and other household goods contained within them a life others could not immediately see. Ever since childhood, her world has been alive to itself. “I have always animated the inanimate in my mind,” Lopez states. She fed the carpet bits of paper and was convinced the shadows in her bedroom were creatures of fantasy.

The whole gang!

It is easy to see these youthful imaginings channeled into Lopez’s work. One glance at her “dust furries,” for which she is best known, reveals that her interests continue to live in the realm of play. Though these meticulously constructed porcelain sculptures layered in polychrome tentacles lack faces and limbs, it is easy to see them galumphing about snuffling for crumbs—or perhaps the scraps of paper Lopez is known to provide the hungry household item.

Shivering Dust Furry with Gold Rocks, 2020

What is easy to overlook—so delightful are her creatures—is the precision with which Lopez is able to execute them. (Her studio, too, is immaculate.) The thoroughness with which the artist tests colors, as well as the excitement she feels toward finding the right tool (like a dental mirror, whose angle allows her to see underneath her pieces without having to touch them) or glue (who knew glue could be cause for such joy!) reveals something that might not initially be betrayed by these anthropomorphized dust bunnies—that is, this really matters to the artist. “That moment of stepping back from the thing that you know to give it a chance to be its real self… are the moments I live for,” she reveals.

Her approach to creativity, too, is serious, as she views play as the means towards finding the right way to say something. It is essential not only to the furries’ (and nubbies’ and dust mops’) success, but to the artist’s philosophy. “Play is the only place you can make mistakes,” she tells me, and mistakes are the only way to innovate. Play is the foundation of learning, whether it's the artist’s students pushing clay to its limits or the artist herself standing in a Kudzu forest, imagining the outer edges of her world expanding to meet the expanse of her creativity. Play is the space in which you are able to see the “real self” everything contains.

Soft Watermelon Dust Furry with Blue Rocks, 2020

Alongside play, the idea of “sympathetic magic,” or the belief that things are imbued with their own history, is essential to understanding an object’s inner life. As of late, the artist has been working with weavers in Oaxaca, Mexico to weave rugs which she has been incorporating into installations, containing both ceramics and textiles. These rugs are purposefully left unfinished, as a symbol of the carpets’ continued making, as if any object within our lives is never finished, but rather is engaged in an endless process of making, constructed of our engagement with it. In their own way, these rugs express their real selves, as rich as their ceramic counterparts’.

So how do we place Lopez’s work in the context of our own inner lives? These rainbow-colored dust monsters insist we are without limit and that the world is something of which to be made—not to be consumed, but to be transformed. Her work is an invitation to arrange ourselves as we wish, to make friends with our environments, and to believe nothing can hold us back—not language, not nationality, not even the inanimate.

More on Linda here.

Ida Floreak

New Orleans, Louisiana

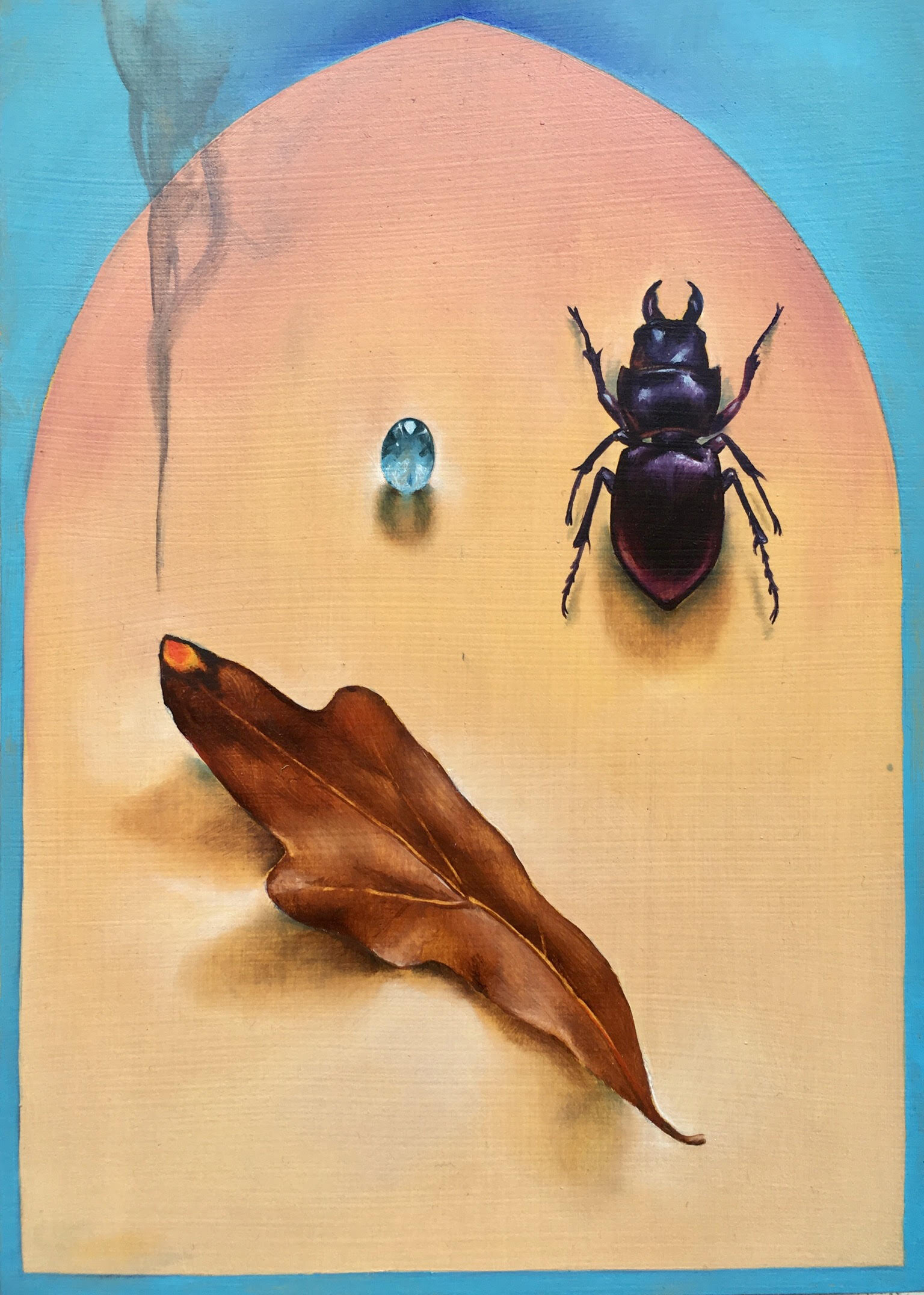

Halo 2, 2017

While I spoke to the painter Ida Floreak she was pinning beetles, a skill she learned while volunteering at New Orleans’s Audubon Butterfly Garden and Insectarium. Outside her studio’s window sat a squawking group of feral parakeets, whose shed feathers sat in a pile on the artist’s desk, alongside one of their fallen’s delicate bird skulls. “I have this library of treasures to draw from,” she says, gesturing at these objects, many of which make their way into her photorealistic arrangements.

Floreak has a fascination with this found flora and fauna, which lie at the center of her work. She describes her interest as a “19th century naturalist’s” sense of wonder, rather than the purposefulness of a modern biologist. “There’s a lot of beauty... and poetry in science. Just because you’re looking for answers doesn’t mean you can’t be in awe,” she says referring to the fact that she prefers her “work to ask questions more than answer them...to leave room for mystery and open endedness.”

Floreak does this by employing a symbolic language devoid of its context—I think of it almost as if a Dutch still life without the table to rest on. Her canvases depict these things—feathers and eggs and leaves, bugs and bones—placed separately, deliberately spaced apart and painted from above, with an occasional arch or halo of light to delineate space. Love Letter to Fra Angelico, however, admits more of a Catholic influence (rather than Dutch Protestantism), as Floreak did spend some of her undergraduate years in Italy. Light, shown through the presence of shadows, is consistent throughout and is perhaps responsible for some of the spiritual feeling of these pieces, as if they are illuminated by the sun beams filtered through a church’s clerestory.

Censer//Beetle, 2020

But denomination is beside the point, as these paintings touch on a more universal feeling. “I’m studying the spirit of these things,” she explains, which accounts for why she uses certain symbols again and again. Rather than explore the biodiversity of beetles (for which, as the quotation goes, God has an “inordinate fondness”) she uses the same model (if you can call it that) for all her paintings. “In my collection I have tons and tons of beetles, but I still keep coming back to this one,” she says holding a small black bug, “because it feels like the essence of a beetle,” or the perfect sign to stand in for all of beetledom.

But her paintings don’t subsist on insects alone. There is a comingling of objects, each with a presence as strong as the beetle’s, which casts a spell. While it's tempting to try to formulate a language from these discrete items, especially as the tradition from which they are born (that is, Catholic iconography) would demand it, it is better to let them wash over you. “They’re little altars,” Floreak says. But altars to what?

While these images are impressive in their technical acumen, they are most interesting in their moments of change, which uses photorealism to transcend reality and build an alternate space in which the potency of spirit is held.

Because they look real, it is as if they have halted life midstep and have harnessed that forward momentum. Smoke, which curls from the tips of dried leaves, as well as droplets of water, cohereing on surfaces, are all that’s needed to have this effect. Instead of the inertness of fruits and flowers in a still life (which in French are aptly called nature mortes, or “dead nature”), they are condensed, saturated with the energy of life. Earth, air, fire, and water are each present, “and in all that, time,” Floreak says, adding a final element. By “evoking a story without there being a narrative,” the paintings become an incantation, a combination of nonsense words that mysteriously coalesce to have a coherent effect.

Love Letter to Fra Angelico, 2017

“New Orleans [is] a place where a lot of religions and spiritualities and world views have come together and informed each other and bled into each other,” Floreak explains. I try to imagine these paintings finding a voice within RISD’s Nature Lab, where the painter spent much of her undergraduate years among taxidermied animals and microscope slides, but somehow I can’t. In New Orleans, “there’s room for magic,” which is precisely what these paintings are: little bits of the miraculousness of life.

More on Ida here.

Phoenix Savage

Tougaloo, Mississippi

The artist Phoenix Savage

I caught multi-media artist Phoenix Savage at a crossroads, a moment in her career when she is assessing her work and figuring out where to go from here. When she first moved to Mississippi in the 1990s, she was on a mission: she had heard about the spate of fires set to African American churches in the South and she wanted to investigate. So she loaded up her pick-up, packed her camera, and began the long drive from New Mexico.

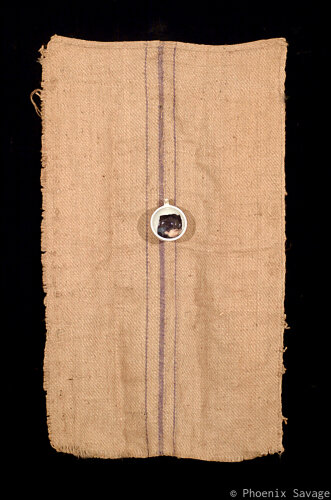

Morning Coffee

She ran out of money in Mississippi, a place she said she admitted she was “scared of ” as it bore the aftermath of the Civil War and Jim Crow like a fresh wound. The state, however, soon became her muse. “I really looked at it from an anthropological eye….all its tumultuous history. The old work was looking at that and finding little bridges to cross over between these divisive sides, looking to bring hidden histories out.” Among those works were Remnants and Morning Coffee, both from a series of eerie, talismanic objects that seem to communicate a spiritual power borne of pain and made of the intensely resonant bric-a-brac one might find in a Betye Saar sculpture. In Morning Coffee, a cup sits at the center of a piece of burlap with what looks like the dregs of that morning’s brew resting at its bottom. At closer inspection, however, we notice what we believed to be grounds are an old photograph of a man peering up at us, either a reflection of ourselves in the coffee’s lees, or else a haunting reminder of someone we have lost who still lingers in our thoughts. Though the impression might be relatable, the deeply personal nature of her material makes it feel as if we have stumbled on someone else’s daily ritual, a cup now cold which once warmed the hands of an individual.

Morning Coffee detail

But these days things are a little different. “I’m physically here in Mississippi, but I’m not sure I’m spiritually here,” Savage laments. Ever since spending her Fulbright in Nigeria in 2012, she has felt more of a pull to the people there. Her most recent work builds on techniques she learned while in Africa, including a method of lost wax casting that has the artist carve directly into wax fashioned around an armature, rather than creating a mold with which the wax can be shaped. This method shortens the production timeline for these bronzes, but in doing so gets rid of all possibility for the object's replication. Only a single object can be made from this lost wax technique.

In fact, much of Savage’s practice centers on a similar irreproducibility. Wax, which has enough integrity to hold its form, but is malleable enough to quickly shed it, is the perfect substance in which to explore this idea. For the Human Touch Project (2012), Savage invited participants at Penn State University to leave a bit of themselves, in the form of touch, in small globules of wax which bore the reminder of their presence in impressions. Each piece is fragile and, of course, as unique as a fingerprint.

Savage thwarts reproduction again in Ambient Void, a sculpture made of thousands of ceramic eggs shells strung up so that at its center is an empty space in the shape of a human body. Though planned with the help of a computer program, which dictated where and how many shells would be placed on each string, the intense labor that went into this work makes it virtually irreproducible. The object’s genesis in technology makes a strong case for individualism: even in our vast digital world, human intervention remains essential.

Ambient Void

At this inflection point for Phoenix Savage, I would argue her purpose as an artist revolves around this thread. In a world which is increasingly global, increasingly interconnected, and increasingly known, her work leaves space for the individual, the complex, and the unique.

More on Phoenix here.