Data Harvest

“Face to Face” with installation artist Jean Shin

In creating his fantastical charcoal drawings, the proto-Surrealist Odilon Redon (who was not a female artist) said that he was attempting to use the “logic of the Visible at the service of the Invisible.” This elegant summation of his practice touches on something central to almost all art: the transformation of that which we cannot see into something which we can, whether it be surreal visions of the subconscious or political and social realities hiding in plain sight.

Chance City (2001-2009)

For installation artist Jean Shin, the invisible is always at the forefront of her thinking. Now, I in no way want you to think that Jean Shin is a Surrealist––in Redon’s terms, she is actually something of the opposite, as she uses the logic of the Invisible at the service of the Visible. Her primary mode is taking the metaphors embedded in daily life and language and translating them into objects, using them in bulk to magnify what we’d otherwise dismiss. The nagging feeling that we might not “measure up” to expectations is physically transformed into hundreds of discarded pant cuffs artfully arranged in Alteration (1999), a reminder that many of us don’t meet the standard of an imagined average height, as an average is “antithetical to our lived experience.” Sweaters unravel to reveal a map of threads that connect networks of friends and acquaintances in Unravelling (2006-2009), and in Chance City (2001-2009), the pursuit of the American Dream solidifies in a house of cards, except these cards are lottery tickets that contain no winning numbers.

MetaCloud (2017)

Shin brings the same sort of impulse to the largest and most inscrutable elements of our daily struggle with the invisible: big data. In MetaCloud (2017), which is now displayed at Facebook’s New York office, Shin takes on the omnipresent metaphor of “the Cloud.” In an elegant repurposing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s slide archive––which they were discarding when Shin intervened––she arranges the original and duplicate images in cascading reels, honoring the invisible work of archivists by maintaining their original groupings. The fact that you can stand at the center of these mobiles and feel yourself immersed in information and images is the visualization of the promise of the Internet as a space without hierarchy, where all information is equally accessible. The utopian vision of the World Wide Web as an agent for democratic dissemination of information is, of course, a fantasy. (Utopia, after all, means “no place.”) “On the Internet we’re so unaware that there is a filter.” Shin hopes the work will “hold Facebook accountable” and make them consider what the consequences of that filter are.

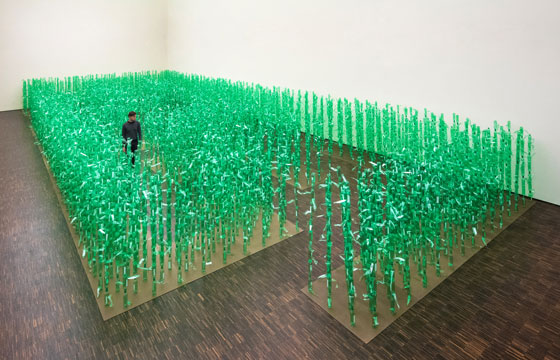

If you talk to anyone in the tech or finance world, you’ll hear them say that data is just numbers until you use it to tell a story. Jean Shin’s work is that story, a look into the “behavioral patterns of people,” and while her data does not come in the form of numbers, it’s certainly revealing of the population from which it is derived, not least because of how she gets her hands on it. Instead of filching data, anonymously and exploitatively, Shin comes by it organically: by asking people to donate. When she asked the community in Davenport, Iowa for green plastic bottles of soda, they gave her what they had consumed. The data “harvested” here for her project MAiZE (2017) was used to make stalks of plastic corn, a “hybrid object that seems natural but is totally artificial” and a comment on the genetic modification of this supercrop. The quantity of bottles donated is just a glimpse into our dependence on corn syrup, as it is the first ingredient in most sodas. That the community in Davenport is dependent on corn both nutritionally and economically is a layered meaning typical of the multi-dimensionality of Shin’s installations, as a work’s location is often an invisible material with which she works.

Alteration (1999)

As she is known to think deeply about place, Shin is an obvious choice when institutions are tasked with commissioning site specific work. When planning Elevated (2016) for the long awaited Second Avenue Subway, she stuck to her theme, but this time using the invisible at the service of the invisible. The story of the Second Avenue Subway is one that is dominated by hope and disappointment. It occurred to Shin that the most poignant way to represent its history was through absence. Her large scale mosaic depicts the outline of the elevated track which ran down Second Avenue until 1942, a spectre against a blue sky. The mosaic and ceramics remind commuters that the El’s removal was at first a sign of hope for an underground replacement, though that hope was quickly replaced by disappointment when no new line materialized. Seventy-five years later, Shin celebrated the hope fulfilled and reclaimed what had been lost.

Elevated (2016)

Odilon Redon took an invisible fantasy and made it reality. Shin is tasked with a more difficult knot to untangle: how to pull an invisible reality into our visual world. Of her installation Surface Tension (2016), Shin speaks of how “action happens on the line” between surface and interior, between past and future, between metaphor and reality. Her work dances merrily on this line, insisting the threshold to the invisible––and here Redon would agree–– is through art.

More on Jean Shin here.