Respect the Hotdog

Or, A Brief History of Gesture

“Face to Face” with painter Ivy Haldeman

Ivy Haldeman is totally serious. Sure, her seven foot tall paintings are of lounging hotdog figures, but who is the artist to judge what a hotdog person does when she doesn’t think she’s being watched?

In her own little world, the hotdog sits with her legs “akimbo,” thumb in a book, twists her hair (or what appears to be “hair,” but is really a plume of sausage casing—did I mention she’s a hotdog?), or leans over to put on her stilettos (wouldn’t you want to look sexy if you were a hotdog?). But across all these paintings, one thing is clear—Haldeman’s subject doesn’t seem to notice she’s a hotdog. Instead she sits happily ensconced in a fluffy wonder bread bun, dreamy and introspective.

Crop, Open Book, Open Bun, Finger Tugs Do, Banana Phone, 2019. Acrylic on Canvas, 24 × 16 1/2 inches / 61 × 41.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

This unselfconsciousness might be the crux of these paintings, what prevents them from inhabiting a commercial or pop sensibility. Unlike the original anthropomorphic sausage painted on the side of a bodega which inspired Haldeman, this hotdog is not meant to convince you to buy a hotdog. It’s meant to convince you you are human.

I know what you’re thinking, but stay with me.

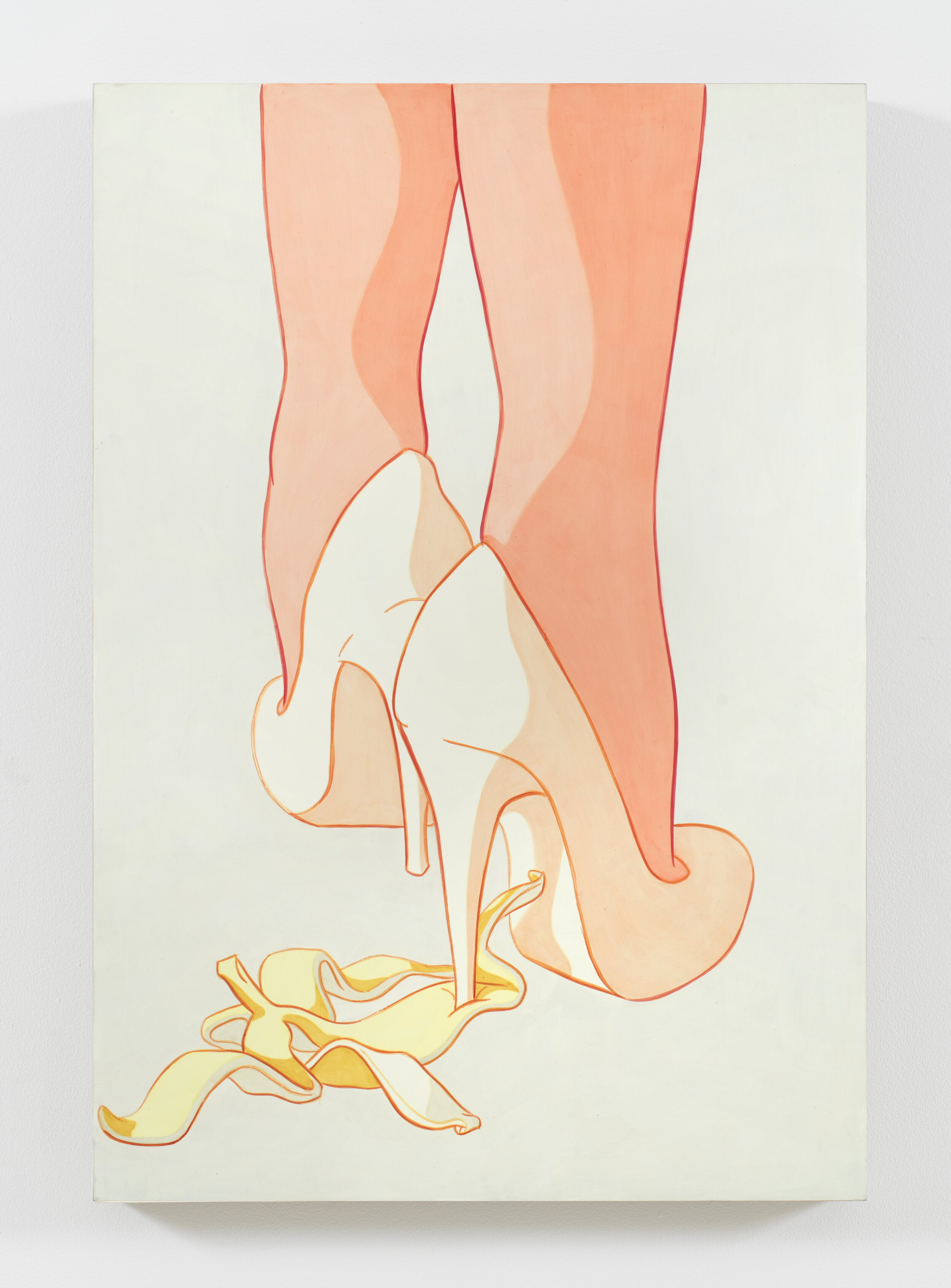

The scope of Haldeman’s visual lexicon is extremely spare. Her hotdogs appear the most often, but are sometimes joined by women’s power suits circa 1985, the classic slapstick banana peel, and human hands which use their appendages like legs, “walking” around on their middle and pointer fingers. But quantity is passed over for the sake of meaning, as each of these motifs speak volumes. Excess seems verboten here, and the artist favors purity of composition—her images are uncluttered, like the clean toll of a bell, whose note cannot be mistaken.

Two Suits, Wrist Bent, Cuff to Pocket (Mauve,Peach), 2019. Acrylic on Canvas, 67in x 60 in / 170.2 x 152.4cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Haldeman is constantly looking at people and the way they hold themselves absentmindedly. She is a master of identifying gesture and looks for its finest examples on the bus, in the pages of books, and even in the mirror. Though her chosen subject is idiosyncratic, it turns out that gesture is not itself without precedent in the history of art. While perusing the oversized art books found on the third floor of the Strand (a blissfully uncrowded part of the bookstore), Haldeman was stunned to see her paintings reflected back at her in a book of Utamaro prints. No, she did not stumble upon a lost trove of Japanese sausage Kabuki, but rather opened the book to find the spiritual ancestor of her hotdog paintings: prints of an array of eighteenth century Japanese women—from geishas to idealized standards—engaging in private moments at their toilettes, like applying makeup or pushing back a strand of hair. (Degas’s bath paintings offer a similar sort of voyeuristic pleasure, in part for their erotic appeal, though I would argue our attraction also has to do with their complete ordinariness, the visceral identification we have with seeing a body performing tasks we move through daily.)

Haldeman works with a similar reverence to those small moments and understands the power of immortalizing them through art. This is perhaps what explains the Haldeman’s interest in an Egyptian encaustic portrait at the Met, an object to which she returns again and again. It depicts a pubescent boy (he seems to be sporting his first mustache) with a surgical gash in his eye, a memento of an injury from which he is recovering. The strangeness of this image—almost two millennia old—is rife with questions. What happened to this boy? Why was he painted in this state? We might want to ask the same questions of our hotdog protagonist, who is equally unflinching (and uncritical) in her own star turn on canvas.

There is something democratic in Haldeman’s hotdog paintings, an insistence that visual culture no longer be codified as a means of communicating power. There is freedom in being able to depict the languid absentmindedness of this sausage, as for centuries commissioning and owning paintings was limited to a certain class of person, and therefore so too was the imagery contained within them. And when it comes to the portraiture of such a class of people, the gestures of power, in fact, are very limited. Contraposto communicates stability, while a raised arm leads us to victory. Even complacent monarchs are always painted with the straight spines of power.

Heels, Peel, 2019. Acrylic on Canvas, 24 × 16 1/2 inches / 61 × 41.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

But gestures in art changed as the market for art expanded. With the rise of the middle class in the seventeenth century Netherlands, for example, painting largely abandoned images of power (though restrained pendant portraits of wealthy merchant couples still existed) in favor of everyday scenes—the images of maids going about their work and men (or women!) carousing, drinking, or playing cards. (That these images were often warnings to the morally depraved is another matter entirely.) Consider our sexy hotdogs as the inheritors of such a history.

But if it’s simply body language Haldeman is after, then why paint hotdogs at all? Like so much of her work, it has to do with recognition, that immediate sense that we understand something corporeally. To put it bluntly, paintings of unsuspecting naked women and images of prostitutes simply do not fly these days—they are dated and remove the viewer from time, tangling us in a mess of intellectualized implications and twenty-first century questions. They might lead us to ask if there is an inherent violence in looking at an image of a naked woman who expects privacy, all the while painting the human body can seem redundant in an age of ubiquitous photography. The hotdog, though it might not appear so, is a neutral zone, a vessel for gesture that is evocative enough of our moment to make sense, but not so evocative as to be nostalgic or anachronistic.

Crop, Feet Touch, Pinky Along Frame, 2019. Acrylic on Canvas, 24 × 16 1/2 inches / 61 × 41.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

I do not think, however, that these works are about consumerism any more than anything made in America in the twenty-first century is, but rather they take consumerism as their given. We’re swimming in our culture, too close to it to be able to critique it. We take consumerism with us whether we’re reading, lounging, or dressing to go out. We are the power suit, the gimmicky banana peel. We are the hotdog.

More on the fabulous Ivy Haldeman can be found here.